Database keys are fundamental to how relational databases work. They define how rows are uniquely identified, how tables relate to each other, and how data integrity is maintained as systems grow. Whether you are designing an OLTP database, modeling analytics data, or preparing for database interviews, understanding database keys is essential.

In this guide, you will learn what database keys are, why they matter, and the different types of keys used in modern database design, with clear explanations and real-world examples.

Key Takeaways

A database key is an attribute or set of attributes that uniquely identifies a row or establishes relationships between tables

Different types of keys serve different purposes, such as uniqueness, relationships, and data modeling clarity

Primary and foreign keys enforce structure and relationships, while other keys support design and normalization

Modern systems often use surrogate primary keys combined with unique business keys for flexibility and performance

Key behavior differs between transactional databases and analytical data warehouses

What is a database key?

A database key is a column or combination of columns used to identify records in a table and define relationships between tables. At its core, a key answers one simple question:

How do we reliably refer to one specific row of data?

In relational databases, tables store many rows that often look similar. Without keys, there would be no reliable way to distinguish one record from another, link related data across tables, or prevent duplicate or inconsistent records.

Why database keys exist

Database keys serve several critical purposes:

- Uniqueness: Ensure that each row can be identified without ambiguity

- Relationships: Connect related tables using well-defined references

- Data integrity: Prevent invalid or orphaned data from entering the system

- Query efficiency: Enable databases to locate and join data efficiently

- Data modeling clarity: Express real-world rules in the schema itself

For example, in a users table, many people may share the same name or country. A key such as user_id allows the database to uniquely identify each user regardless of overlapping attributes.

Keys and functional dependency (important concept)

In relational theory, a key is closely tied to functional dependency. A key functionally determines all other attributes in the table.

In simple terms:

- If you know the key value, you can determine every other column in that row

- No two rows can share the same key value and still represent different entities

This concept is the foundation of normalization and explains why keys are central to good database design.

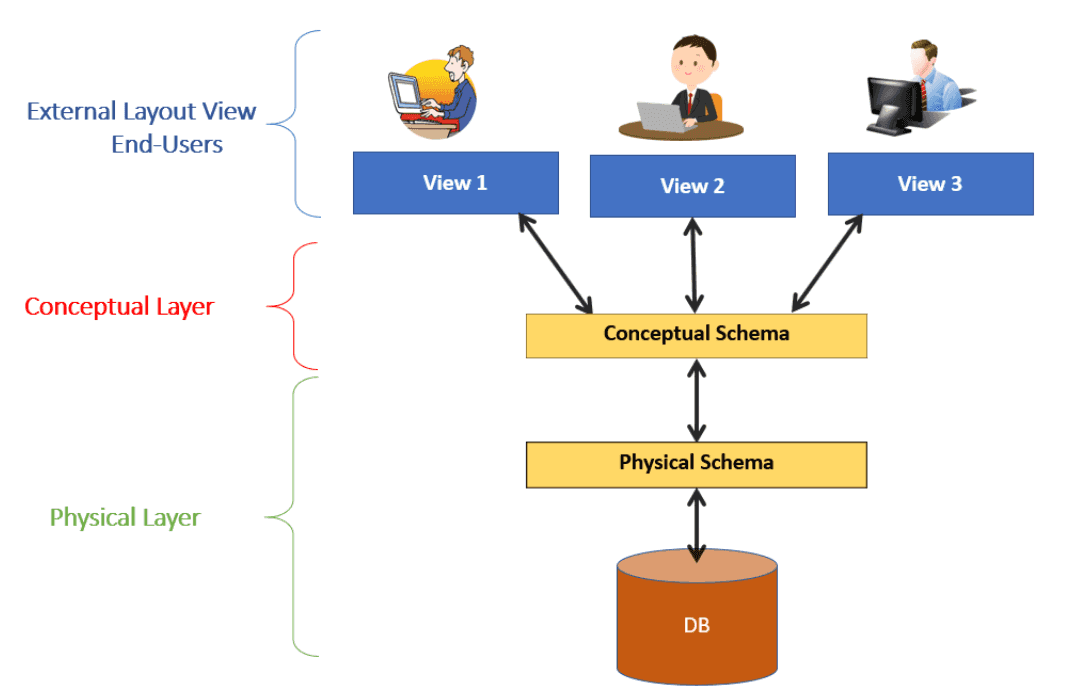

Keys are a logical concept, not just a SQL feature

It is essential to understand that keys are logical modeling concepts first. SQL constraints like PRIMARY KEY or FOREIGN KEY are how databases enforce keys, but the idea of a key exists even before you write SQL.

This distinction becomes especially important in:

- Data warehouses where constraints may not be strictly enforced

- Data modeling and schema design discussions

- Interview and system design scenarios

In the next section, we’ll clear up a common source of confusion by explaining how keys, constraints, and indexes differ, and how they work together in real databases.

Keys vs Constraints vs Indexes: What’s the Difference?

One of the most common sources of confusion in database design is the difference between keys, constraints, and indexes. These terms are often used interchangeably, but they serve distinct roles and operate at different levels of the database system.

Understanding this distinction is important for both correct schema design and performance tuning.

Keys: the logical identity of data

A key is a logical concept used in data modeling. It represents how a row is identified or how tables relate to one another.

For example:

user_idis the key that identifies a userorder_idlinks an order to a specific user

Keys describe what must be true about the data, independent of how the database enforces or stores it.

You can design keys on paper before writing a single SQL statement. This is why keys are central to database normalization, ER diagrams, and system design discussions.

Constraints: rules enforced by the database engine

A constraint is how a database enforces rules defined by keys and business logic.

Common key-related constraints include:

PRIMARY KEYUNIQUEFOREIGN KEY

Constraints tell the database:

- What values are allowed

- What relationships must be valid

- What actions to take when data is inserted, updated, or deleted

For example:

- A

PRIMARY KEYconstraint enforces uniqueness and non-nullability - A

FOREIGN KEYconstraint ensures referenced data exists in another table

Constraints protect data integrity at write time, preventing invalid data from entering the system.

Indexes: physical structures for performance

An index is a physical data structure that improves query performance. Indexes help the database quickly locate rows without scanning the entire table.

Key points to understand:

- Indexes are optional for correctness but critical for performance

- Indexes can exist without constraints

- Constraints often create indexes automatically, but not always

For example:

- A primary key usually creates a unique index behind the scenes

- You can create an index on a column that is not a key at all

Indexes answer the question:

How can the database find this data faster?

Common misconceptions (and clarifications)

- A primary key is not the same as an index

A primary key is a rule; an index is an implementation detail. - A unique index is not always the same as a unique constraint

A unique constraint enforces data integrity; a unique index mainly enforces uniqueness for performance purposes, depending on the database. - Removing an index does not remove a key

The logical key still exists in the data model, even if enforcement or performance changes.

Why this distinction matters in practice

Understanding the difference helps you:

- Design clean, normalized schemas

- Avoid accidental performance regressions

- Reason correctly about warehouse vs OLTP behavior

- Explain tradeoffs in interviews and design reviews

With this foundation in place, we can now look at the different types of database keys, starting with the most important one: the primary key.

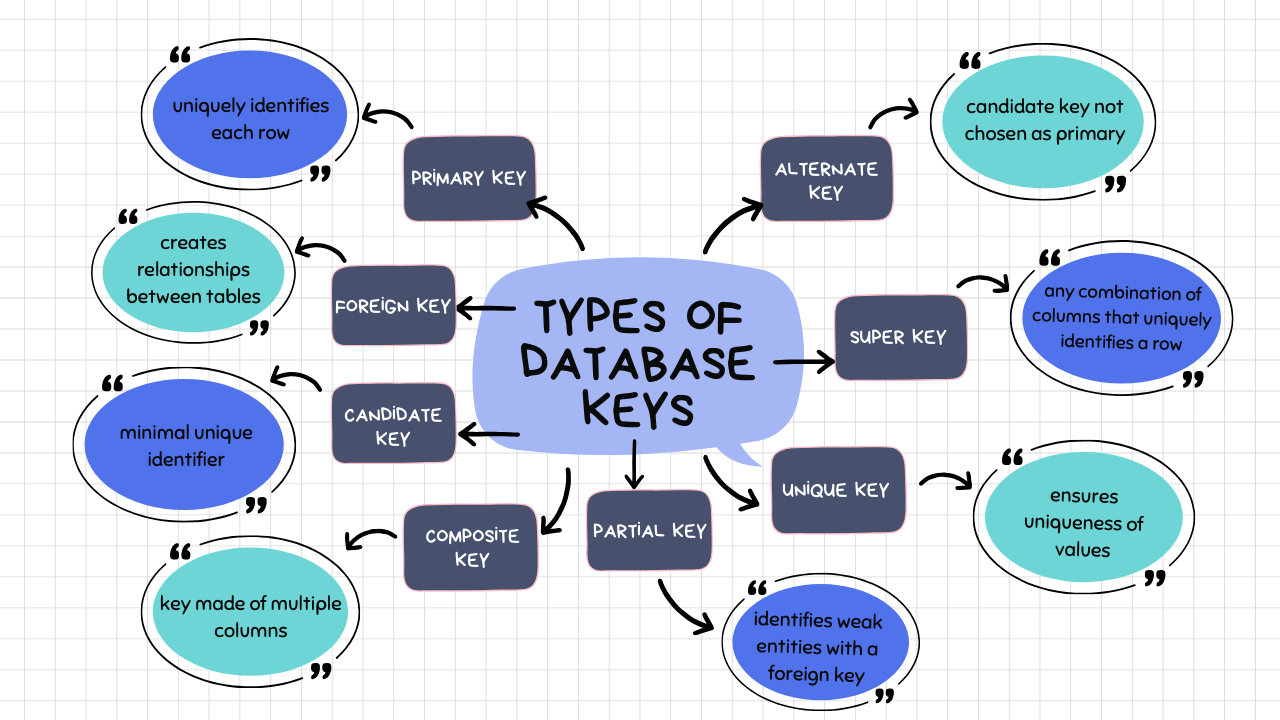

The Main Types of Database Keys (with Examples)

Different types of database keys exist because databases solve multiple problems at once: identifying data, enforcing rules, and modeling real-world relationships.

Before exploring each one in detail, here is a quick overview of the most commonly used database key types.

Types of database keys include:

- Primary Key – Uniquely identifies each row in a table

- Foreign Key – Creates a relationship between tables

- Candidate Key – A minimal set of columns that can uniquely identify a row

- Alternate Key – A candidate key not chosen as the primary key

- Super Key – Any combination of columns that uniquely identifies a row

- Unique Key – Ensures uniqueness of values in a column or set of columns

- Composite (Compound) Key – A key made up of more than one column

- Secondary Key (Non-Unique Key) – Used for searching or grouping data, not uniqueness

- Partial Key – Used to identify weak entities in combination with a foreign key

Each of these keys plays a different role in database design. In the sections below, we’ll look at how each key works, when to use it, and common mistakes to avoid.

We’ll start with the most fundamental key and build from there.

Primary Key

A primary key uniquely identifies each row in a table. No two rows can share the same primary key value, and the primary key must always have a value.

In most relational databases, a primary key implies:

- Uniqueness

- Non-nullability

- A single primary key per table

Example

plaintext language-sqlCREATE TABLE users (

user_id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

email TEXT,

created_at TIMESTAMP

);

Here, user_id uniquely identifies each user, even if multiple users share the same email or creation date.

When to use a primary key

- Every table should have one

- It should be stable and rarely change

- It should be as small and simple as possible

Common mistake

Using a mutable attribute like email or phone number as the primary key. If that value changes, all related foreign keys must be updated, which is risky and expensive.

Foreign Key

A foreign key is a column (or set of columns) that references a primary key or unique key in another table. It establishes a relationship between tables and enforces referential integrity.

Example

plaintext language-sqlCREATE TABLE orders (

order_id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

user_id BIGINT,

FOREIGN KEY (user_id) REFERENCES users(user_id)

);

Each order must reference a valid user. The database can prevent:

- Orphaned records

- Invalid references

- Inconsistent relationships

Why foreign keys matter

- They encode relationships directly into the schema

- They protect data integrity automatically

- They document how tables are meant to be joined

Practical note

In some data warehouses, foreign key constraints may not be enforced, but modeling them is still important for clarity and optimization.

Candidate Key

A candidate key is any minimal set of columns that can uniquely identify a row. A table can have multiple candidate keys, but only one is chosen as the primary key.

Example

In a users table:

user_idemail

Both could uniquely identify a user, making them candidate keys.

Key properties

- Must be unique

- Must be minimal (no unnecessary columns)

- One candidate key becomes the primary key

Why candidate keys matter

They help you reason about alternative ways to identify data and guide normalization decisions.

Alternate Key

An alternate key is a candidate key that was not selected as the primary key.

Example

If user_id is the primary key and email is also unique:

emailis an alternate key

In SQL, alternate keys are typically enforced using UNIQUE constraints.

Why alternate keys are useful

- Preserve business rules (for example, one account per email)

- Allow efficient lookups without exposing primary keys

- Support integrations and external references

Super Key

A super key is any combination of columns that uniquely identifies a row, even if the combination includes extra attributes.

Example

(user_id)(user_id, email)(user_id, created_at)

All of these uniquely identify a user, but only (user_id) is minimal.

Important distinction

- Every candidate key is a super key

- Not every super key is a candidate key

Super keys are mostly a conceptual tool used in database theory and normalization, but understanding them helps clarify why minimal keys matter.

Unique Key (Unique Constraint)

A unique key ensures that values in a column or set of columns are unique across rows.

Example

plaintext language-sqlCREATE TABLE users (

user_id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

email TEXT UNIQUE

);

Primary key vs unique key

- A table can have only one primary key

- A table can have multiple unique keys

- Primary keys cannot be null

- Unique keys may allow nulls, depending on the database

Common use cases

- Enforcing business rules

- Protecting natural or business identifiers

- Supporting alternate keys

Composite Key (Compound Key)

A composite key is a key made up of more than one column.

Example

plaintext language-sqlCREATE TABLE order_items (

order_id BIGINT,

line_number INT,

PRIMARY KEY (order_id, line_number)

);

Here, neither order_id nor line_number alone is sufficient. Together, they uniquely identify a row.

When composite keys make sense

- Junction tables (many-to-many relationships)

- Weak entities

- Naturally multi-attribute identifiers

Tradeoff

Composite keys improve data correctness but can complicate joins and ORM usage if overused.

Secondary Key (Non-Unique Key)

A secondary key is a column used for searching or grouping data, but does not uniquely identify a row.

Example

countryin auserstablestatusin anorderstable

Multiple rows can share the same secondary key value.

Important clarification

- A secondary key is a logical concept

- An index is the physical structure often used to optimize queries on secondary keys

Secondary keys are about access patterns, not identity.

Partial Key (Weak Entity Key)

A partial key is used to identify weak entities that cannot be uniquely identified on their own.

Example

item_numberinorder_items

item_number alone is not unique globally. It becomes unique only when combined with its parent key (order_id).

Partial keys are common in:

- Weak entities

- Hierarchical data models

- Composite primary keys

With all key types covered, the next step is understanding modern key design choices, especially the tradeoff between natural and surrogate keys.

Natural Key vs Surrogate Key (and Business Keys)

One of the most important decisions in database design is choosing what kind of primary key to use. In practice, this usually comes down to a choice between natural keys and surrogate keys. Understanding the tradeoffs between them is essential for building scalable and maintainable systems.

What is a natural key?

A natural key is a key that comes from the real world and has business meaning. It already exists in the domain and uniquely identifies an entity without being artificially generated.

Examples of natural keys

- Email address for a user

- ISBN for a book

- Social security number

- Product SKU

Natural keys often look appealing because they are meaningful and already unique.

Advantages of natural keys

- No additional column is required

- Easy to understand and explain

- Reflect real-world business rules directly in the schema

Problems with natural keys

Despite their appeal, natural keys often cause problems over time:

- They can change: Email addresses, phone numbers, and even SKUs change more often than expected.

- They are often wide: String-based keys increase index size and slow joins.

- They tightly couple systems: Changing a natural key can ripple across multiple tables and services.

For these reasons, natural keys are rarely used as primary keys in large or long-lived systems.

What is a surrogate key?

A surrogate key is an artificially generated identifier with no business meaning. It exists solely to identify a row.

Common surrogate key types

- Auto-incrementing integers

- Database sequences

- UUIDs

- ULIDs

Surrogate keys are the most common choice for primary keys in modern relational systems.

Advantages of surrogate keys

- Stability: They never change

- Performance: Small numeric keys are efficient for indexing and joins

- Decoupling: Business rules can evolve without breaking relationships

- Simplicity: Clean foreign key relationships across the schema

Downsides of surrogate keys

- They carry no business meaning

- You still need additional constraints to enforce real-world uniqueness

- Poor choices (for example, random UUIDs in some databases) can affect index performance

What is a business key?

A business key is a real-world identifier that the business cares about and expects to be unique, such as an email address or customer number.

In modern designs:

- The surrogate key is used as the primary key

- The business key is enforced using a

UNIQUEconstraint

Example

plaintext language-sqlCREATE TABLE users (

user_id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

email TEXT UNIQUE

);

This pattern combines:

- Stability and performance of surrogate keys

- Data integrity of natural identifiers

Natural vs surrogate key: which should you choose?

In most real-world systems, the best practice is:

- Use a surrogate key as the primary key

- Enforce business rules using unique constraints

- Avoid using mutable business data as a primary key

Natural keys can work well in small, stable domains, but surrogate keys scale better as systems grow and requirements change.

Special note for distributed systems

In distributed or event-driven architectures:

- Auto-incrementing keys may become a bottleneck

- UUIDs or ULIDs are often used to avoid coordination

The right choice depends on workload, scale, and database engine.

Next, we’ll look at how keys behave differently in analytical data warehouses compared to transactional databases.

Choosing the Right Key (A Practical Design Checklist)

Choosing the right key is less about memorizing definitions and more about making good design tradeoffs. A poor key choice can lead to performance issues, fragile schemas, and painful migrations later. A good key choice keeps your database stable as data volume and usage grow.

The checklist below reflects how keys are chosen in real production systems, not just textbook examples.

1. Does the key uniquely identify a row?

This sounds obvious, but it’s the most common failure point.

A key must:

- Identify exactly one row

- Never collide with another record

- Remain valid over time

If uniqueness depends on assumptions like “this value will probably never repeat,” it is not a safe key.

2. Can the key change in the real world?

Keys should be as immutable as possible.

Avoid keys based on:

- Email addresses

- Phone numbers

- Usernames

- Business labels that may be reissued or corrected

Even if a value is unique today, business requirements change. Keys that change force cascading updates across foreign keys, indexes, and downstream systems.

3. Is the key small and efficient?

Key size matters more than many people realize.

Smaller keys:

- Reduce index size

- Improve join performance

- Lower memory and cache pressure

This is why numeric surrogate keys are so common. Wide string-based keys increase storage and slow down joins, especially at scale.

4. Will the key be heavily used in joins?

Primary keys are often:

- Referenced by multiple foreign keys

- Used in joins across many queries

If a column is going to be joined constantly, it should be:

- Stable

- Indexed

- Easy for the database optimizer to work with

This is another reason surrogate keys tend to outperform natural keys in large schemas.

5. Do you need to enforce business rules separately?

A common and effective pattern is:

- Use a surrogate key as the primary key

- Enforce business uniqueness with a unique constraint

This separates concerns:

- The primary key handles identity and relationships

- The unique constraint handles business correctness

This approach keeps schemas flexible without sacrificing data integrity.

6. Are you designing for scale or distribution?

In distributed systems, key choice affects more than just uniqueness.

Consider:

- Auto-incrementing keys may become contention points

- UUIDs avoid coordination but can affect index locality

- Ordered identifiers (like ULIDs) can balance both concerns

The right choice depends on your database engine and workload, but it should be intentional.

7. Is the key easy to explain and reason about?

A good key should make sense to:

- Developers

- Data analysts

- Future maintainers

If a key requires constant explanation or special handling, that complexity will spread throughout the system.

Summary rule of thumb

In most production systems:

- Use a surrogate primary key

- Keep it small and immutable

- Add unique constraints for real-world identifiers

- Avoid encoding business meaning into primary keys

This approach consistently leads to simpler schemas and fewer long-term problems.

Next, we’ll cover how keys behave differently in analytical data warehouses compared to transactional databases.

Keys in Analytical Databases and Data Warehouses

Keys play a different role in analytical databases and data warehouses than they do in transactional (OLTP) systems. While the concepts of primary keys and foreign keys still matter, how they are enforced and used changes significantly.

Understanding this difference is important if you work with systems like Snowflake, BigQuery, Redshift, or Databricks.

How OLTP databases use keys

In transactional databases such as PostgreSQL or MySQL, keys are central to correctness:

- Primary and foreign key constraints are actively enforced

- Invalid inserts or updates are rejected

- Keys protect referential integrity at write time

- Indexes backing keys are critical for point lookups and joins

In OLTP systems, keys are both a logical design tool and a hard enforcement mechanism.

How data warehouses treat keys

Most analytical databases prioritize:

- High-throughput ingestion

- Large-scale scans

- Flexible schema evolution

As a result, many warehouses:

- Support primary and foreign keys as metadata

- Do not always enforce constraints at write time

- Use keys primarily for query planning and optimization

This does not mean keys are unimportant. It means their role shifts from enforcement to modeling and optimization.

Primary keys in warehouses

In data warehouses:

- A primary key often documents the intended grain of a table

- It helps humans and tools understand what a row represents

- Query optimizers may use primary key information to improve join strategies

However, duplicate rows are usually not automatically rejected unless additional logic is added.

Practical implication

You must ensure uniqueness through:

- Upstream data pipelines

- Deduplication logic

- Controlled ingestion processes

Foreign keys in warehouses

Foreign keys in analytical systems:

- Often describe logical relationships rather than enforced ones

- Help document star and snowflake schemas

- Improve readability and data modeling clarity

In practice, joins in warehouses rely on data correctness, not constraint enforcement.

Why modeling keys still matters in analytics

Even when not enforced, keys are valuable because they:

- Define the grain of fact tables

- Clarify relationships between facts and dimensions

- Improve data quality checks and testing

- Enable better query optimization in some engines

Well-modeled keys make analytical systems easier to understand, maintain, and scale.

Common warehouse-specific patterns

- Surrogate keys for dimension tables

- Composite keys for fact tables with natural multi-column grain

- Soft enforcement of uniqueness using SQL tests or transformation logic

- Late-arriving data handled through merge and deduplication strategies

Keys guide these patterns even when enforcement is external to the database engine.

Key takeaway for analytics systems

In transactional databases, keys prevent bad data.

In analytical databases, keys describe correct data.

Both uses are important, but they require different expectations and responsibilities.

Next, we’ll look at the most common mistakes engineers make with database keys and how to avoid them.

Common Mistakes and Gotchas with Database Keys

Most problems with database keys don’t come from misunderstanding definitions. They come from subtle design decisions that seem reasonable early on but cause issues as systems grow. Below are the most common mistakes engineers make with database keys, along with why they matter.

Using mutable data as a primary key

One of the most frequent mistakes is using values that can change over time as primary keys.

Examples include:

- Email addresses

- Phone numbers

- Usernames

- Business codes that may be reissued

When a primary key changes, every foreign key reference must change with it. In large systems, this leads to cascading updates, broken references, and operational risk.

Better approach

Use a stable surrogate key as the primary key and enforce business rules with a unique constraint.

Skipping primary keys in staging or analytics tables

It’s common to hear:

“This is just a staging table”

“This is analytics data, we don’t need keys”

While enforcement may be relaxed, not modeling keys at all makes it harder to:

- Detect duplicates

- Define table grain

- Reason about joins

- Write reliable transformations

Even in warehouses, defining a logical primary key improves clarity and data quality.

Overusing composite primary keys

Composite keys are valid and sometimes necessary, but overusing them can make schemas harder to work with.

Problems include:

- Verbose joins

- ORM limitations

- More complex foreign key definitions

Composite keys work best when the entity is naturally identified by multiple attributes, such as junction tables or weak entities. For general-purpose entities, surrogate keys are often simpler.

Confusing unique constraints with primary keys

A unique constraint and a primary key both enforce uniqueness, but they are not interchangeable.

Common confusion:

- Assuming a unique constraint replaces the need for a primary key

- Forgetting that a table can have only one primary key

- Ignoring null-handling differences across databases

Primary keys define row identity. Unique constraints enforce business rules. Both usually belong in a well-designed schema.

Forgetting to enforce business uniqueness

When using surrogate keys, engineers sometimes forget to add unique constraints for real-world identifiers.

Example:

- A

userstable with a surrogateuser_id - No uniqueness constraint on

email

This allows duplicate users that violate business expectations.

Rule of thumb

Surrogate keys do not replace business rules. They separate them.

Choosing a key without considering access patterns

Keys influence performance as much as correctness.

Mistakes include:

- Using wide string keys in high-join workloads

- Ignoring index locality and key ordering

- Choosing random identifiers without understanding their impact

Key design should consider:

- How often the key is joined

- How often it is queried

- How data is inserted and updated

Treating keys as purely theoretical concepts

Keys are sometimes taught as abstract DBMS theory, but they have real operational consequences.

Poor key choices can:

- Slow down queries

- Complicate migrations

- Increase storage costs

- Break downstream systems

Good key design balances theory with practical system behavior.

Quick takeaway

Most key-related problems are not caused by missing features, but by underestimating how long schemas live and how systems evolve. Designing keys defensively saves time and pain later.

FAQs

What is the difference between a primary key and a foreign key?

Can a table have more than one candidate key?

What is the difference between a candidate key and a super key?

What is the difference between a primary key and a unique key?

Are primary and foreign keys enforced in data warehouses?

About the author

Team Estuary is a group of engineers, product experts, and data strategists building the future of real-time and batch data integration. We write to share technical insights, industry trends, and practical guides.